African-American Secular Music–Part Two

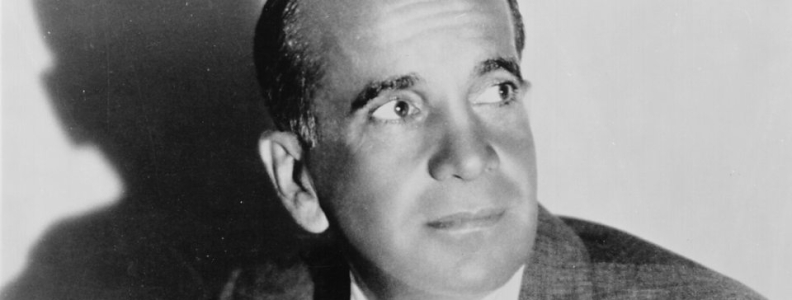

In the last post, we ended it by explaining that Al Jolson created a new character, called Gus.

In this post, we want to explore how the African-American community reacted to Jolson and Gus in blackface.

The African-American community did not like blackface, in general, as a good way to perform; they accepted blackface as a way to get their music more widely distributed to white audiences. The process at the time would be accomplished in two steps: in the first step, a white performer in blackface would attract white audiences and get them accustomed to the sound of the music. The next, incremental step would be to transition from white performers like Al Jolson to black performers like Louis Armstrong.

But something unexpected occurred; specifically, when it came to Jolson, black audiences opened their arms and hearts and accepted Jolson as one of their own. We believe that Jolson’s special place in black culture started with his honest intent to win over white audiences to black music.

According to the St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture: “Almost single-handedly, Jolson helped to introduce African-American musical innovations like jazz, ragtime, and the blues to white audiences…. [and] paved the way for African-American performers like Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller and Ethel Waters… to bridge the cultural gap between black and white America.”

Jazz historian Amiri Baraka wrote, “the entrance of the white man into jazz…did at least bring him much closer to the Negro.” He points out that “the acceptance of jazz by whites marks a crucial moment when an aspect of black culture had become an essential part of American culture.”

However, there was also a second element to the story. Wikipedia notes that “Jolson’s legacy as the most popular performer of blackface routines was complemented by his relationships with African-Americans and his appreciation and use of African-American cultural trends.”

At this point, let’s repeat a quote from a previous post: “When one hears Jolson’s jazz songs, one realizes that jazz is the new prayer of the American masses, and Al Jolson is their cantor.”

Wikipedia provided the following pertinent information about Jolson:

“While growing up, Jolson had many black friends, including Bill Robinson, who became a prominent tap dancer. As early as 1911, at the age of 25, Jolson was noted for fighting discrimination on Broadway and later in his movies:

- “at a time when black people were banned from starring on the Broadway stage,” he promoted the play by black playwright Garland Anderson which became the first production with an all-black cast produced on Broadway;

- he brought an all-black dance team from San Francisco that he tried to feature in his Broadway show;

- he demanded equal treatment for Cab Calloway, with whom he performed a number of duets in his movieThe Singing Kid.”

Wikipedia provided an account of Jolson’s attachment to black performers:

“Al Jolson once read in the newspaper that songwriters Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, neither of whom he had ever heard of, were refused service at a Connecticut restaurant because of their race. He immediately tracked them down and took them out to dinner, ‘insisting he’d punch anyone in the nose who tried to kick us out!’ According to biographer Al Rose, Jolson and Blake became friends.”

Later, at Jolson’s funeral, Sissle, who was President of the Negro Actors Guild, paid tribute to his friend by attending as a representative of the Guild.

Wikipedia also informs us that “British performer Brian Conley, former star of the 1995 British play Jolson, stated during an interview, ‘I found out Jolson was actually a hero to the black people of America. At his funeral, black actors lined the way, they really appreciated what he’d done for them.’ ”

Wikipedia captured the recollections of Jeni LeGon, a black female tap dance star: “But of course, in those times it was a ‘black-and-white world.’ You didn’t associate too much socially with any of the stars. You saw them at the studio, you know, nice—but they didn’t invite. The only ones that ever invited us home for a visit was Al Jolson and [his wife] Ruby Keeler.”

Even as late as 1927, when the movie The Jazz Singer was released, “Many in the black community welcomed The Jazz Singer and saw it as a vehicle to gain access to the stage. Audiences at Harlem’s Lafayette Theater cried during the film, and Harlem’s newspaper, Amsterdam News, called it ‘one of the greatest pictures ever produced.’ For Jolson, it wrote: ‘Every colored performer is proud of him.’

Film historian Charles Musser notes that “African Americans’ embrace of Jolson was not a spontaneous reaction to his appearance in talking pictures. In an era when African Americans did not have to go looking for enemies, Jolson was perceived a friend.”

In today’s terminology, Jolson became a Brother of another color.

We would like to discuss one more aspect of Jolson’s integration into the black community, namely the fact that some black performers copied Jolson’s onstage style. Quoting again from Wikipedia:

“Jolson’s physical expressiveness also affected the music styles of some black performers. Music historian Bob Gulla writes that ‘the most critical influence in Jackie Wilson’s young life was Al Jolson.’ He points out that Wilson’s ideas of what a stage performer could do to keep their act an ‘exciting’ and ‘thrilling performance’ was shaped by Jolson’s acts, ‘full of wild writhing and excessive theatrics.’ Wilson felt that Jolson ‘should be considered the stylistic [forefather] of rock and roll.’ “

With all of the information in this post as background, now let’s go back to opening night of Sinbad on February 14, 1918. George Gershwin had not yet written “Swanee” with Irving Caesar; the only Jolson interpolation in the initial run that is remembered today was Jean Schwartz’ great standard, “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody.”

We have a number of versions that we will post separately this afternoon, including the March 13, 1918 recording by Jolson which remains true to the Broadway orchestration; Jolson’s 1928 recording which introduced a small jazz band arrangement; the 1956 version by Jerry Lewis with a big band backup; and the 1961 version by Aretha Franklin with a soul arrangement.